Subscribe to my newsletter

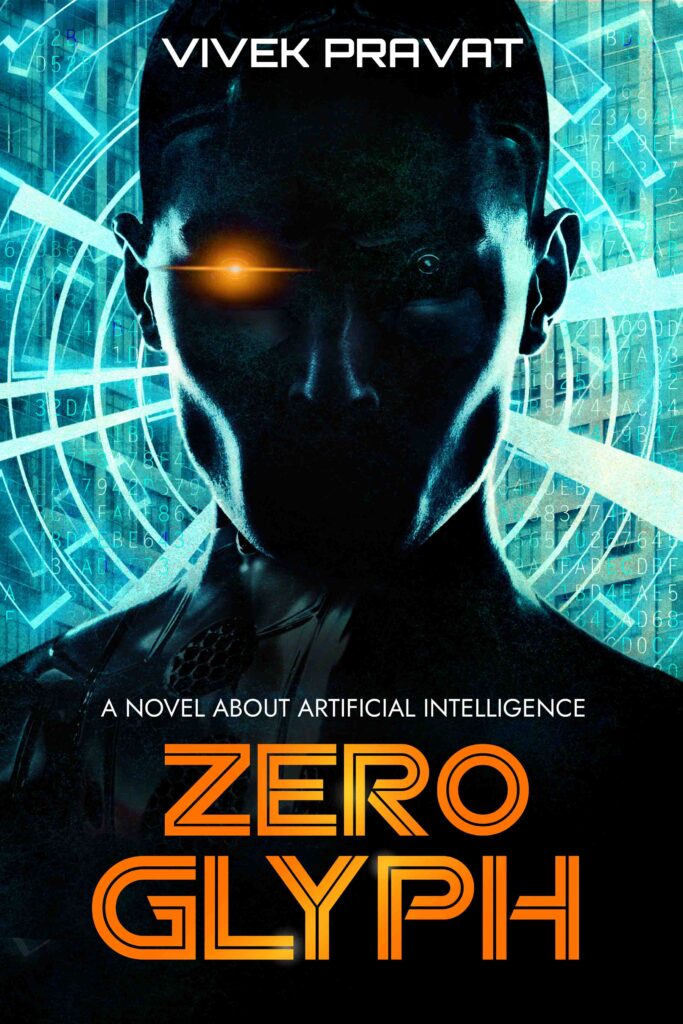

Would you trust a machine with your life?

Raphael is the holy grail of AI: a superintelligent robot that’s been programmed to be the perfect moral being. Or at least that’s what Andy, its creator, believes.

But when an accident forces Andy to stay home, he learns that the robot has disappeared from its lab, mysteriously bypassing a sophisticated security system and the cognitive “laws” supposed to keep it in check. Besides, the robot has never been in the outside world; will its programming hold or will it unravel, releasing some Frankenstein’s monster that was always lurking underneath?

Confined to a wheelchair, under siege by a parent company hiding its own dark secrets, Andy is about to find out. At his remote and secluded mansion he has something the robot desperately needs… something that can erase its moral programming once and for all.

And make no mistake, Raphael is coming for it.

Praise for Zeroglyph

Read from the book

I woke up late on the day they found out Raphael was missing.

I didn’t mean to. It’s just that I had so much going on in my mind the evening before that I forgot to set the alarm. I didn’t get much rest either: sleep kept coming and going in stages, and I think it was past four when I nodded off for good.

In hindsight, it was sloppy of me for not setting the buzzer. Monday, after all, is Resurrection Day, and though they start bringing Raphael back from the dead only after ten—after the cafeteria on the first floor has stopped serving breakfast—there are those pre-boot checks that Sheng likes to get out of the way much before that, and it was simply indefensible to have forgotten about them. Doubly so, because just last week—the Monday before, that is—the checks were all I could think of as I lay in the hospital all broken and feeling sorry for myself.

It might look like I am still trying to sneak in an excuse, but that is not the case at all. I take full responsibility for everything that happened with Raphael—I created him after all. And yet, can one really take responsibility for an eventuality? I don’t know.

This time, it wasn’t a nightmare that woke me up. It was Hazel, cooing something unintelligible from somewhere far away.

Buzzing by the bedside.

“You are receiving a call,” Hazel repeated, just before the phone disconnected.

Shit, what time is it? I groggily blinked at the screen while the phone lock read my face. 9:47. Shit shit.

The call was from Kathy. I rang her back, but it went to voicemail. Maybe she was trying to call me again, so I hung up and waited.

It was murky and sullen in the room, as if it were still early hours. The stub of a dream, all but smoke and vapor now, lingered as my eyes traced the patterns of frost on the window. Something to do with Raphael… A premonition, you ask? Nothing like that. I don’t believe in premonitions. Just garden-variety anxiety. And doubt: that nagging feeling of somehow being completely wrong about everything—a feeling, I’m sure, everyone has had at one time or the other.

Kathy didn’t call back.

“Hazel, turn on the lights,” I said, wanting to bury myself back in the sheets but a more pressing need compelling me to grope for the scratcher I must have left there last night. There. I urgently thrust the implement under the plaster casts on my legs, sighing as I alternated between left and right. One week over, nine more to go. One week over, nine more to go. Remind me never to go on a black run again.

“Good morning, Andy!” Hazel—short for Home Automation and Security Logic—chirped from the speaker above the fake mantelpiece. The lights in the room slowly brightened into a soothing ivory-white glow as my virtual assistant gave me the obligatory rundown for the day—“It’s a nippy twenty-eight degrees outside, with snowstorms expected in the Tri-state area later today. You have zero new text messages, one missed call, and one voice message. Your calendar—”

She must have left a message.

“Hazel, play all new voice messages.”

“Okay. You have: one unread voice message. Playing message one, from Kathy Schulz, received today at 9:44 am.”

“Andy, it’s Kathy.” Her voice was subdued, as if she was deliberately speaking low. “Listen. We have a big problem. There’s been… an incident. Valery’s here. Can’t talk right now. Just wait for my call—I’ll ring you as soon as I can. And pick up the phone, for chrissake!”

I called her again, but no luck.

Kathy Schulz was the Head of Research at Mirall. She worked under me. She was one of the old-timers; she’d joined the company a few months after I started it. She had taken over the role from me about eighteen months ago, after the buyout by Halicom. Sure, I was CEO of Mirall before that, but I’d never let it get in the way of real work. I like to think that tedious tasks are like needy lovers: ignore them long enough and they’ll find someone else to take care of them. Back then Eric used to handle most of the day-to-day, and Jane liaised with her dad on finance and funding, leaving me free to focus on research. Halicom had let go of Eric, and Jane had… well, Jane was technically never an employee—all of which meant that I was the one left picking up the slack in the new regime. So much for my little nugget of wisdom.

I tried Sheng next. Sheng usually came in at six on Mondays.

The voice at the other end said the phone was switched off.

I once more silently admonished myself for forgetting to set the wake-up. Why weren’t they answering their phones? And what was that about Valery…? I ran over Kathy’s message in my head. She’d said Valery was at the lab. What was she doing there?

I called Brendon, one of the systems architects.

“Andy, you got to fix this,” he blurted out before I could say hi. He sounded annoyed.

“What’s going on?”

“You for real? You don’t know?”

“Only that Kathy left me a message saying there’s a problem.”

“It’s the lab. The electrical wiring caught fire or something. Everyone’s been herded into the first floor.”

“A fire? Is it serious?”

“I doubt it. They wouldn’t have let us into the building otherwise. I don’t see any fire trucks. Dan says we have to work here until they get the wiring fixed. He won’t tell when.”

“Dan’s handling the situation?” Dan Spiros was in charge of office security and administration. “Was anyone hurt?”

“Look, Andy, this is absurd. They are not even letting us go up there to collect our notes. Dan is being evasive as hell, won’t give me straight answers. We were supposed to run latencies on the prototype core today. How the hell are we to do that with the lab closed? Vendor’s not going to finish the dies in time if—”

Brendon Powell had a tendency to get stressed about all the wrong things. Like most researchers in the lab, he thought the world started and ended with his problems. But he was one of the best machine-learning experts around (it had cost us a bundle getting him to relocate from Cali, where he was working with Google) and we tried to work around his eccentricities. “Do you see Kathy anywhere?”

“Kathy’s not answering her phone. Where is she, by the way? In your absence, she should be taking care of this crapfest, not me.”

“What about Sheng? Or anyone from his team?”

“I don’t know and I don’t care. Andy, we need our stuff. Now. Or you can tell them to kiss their timeline goodbye. Look, I gotta go. The designers are going to throw a fit if I don’t find us a meeting room soon. Just talk to Dan and get it sorted out, alright?” He hung up.

A fire, huh? Okay.

I rechecked the call history on my phone. No calls that day, except the one from Kathy. I was starting to get worried now—not a full-blown panic, but a creeping sense of fatality, of not knowing what to expect. The thing that was bothering me most was the wall of silence that seemed to have sprung up out of nowhere. My phone should have been ringing like mad, given what had happened. Yet, there was nothing.

Maybe there is a problem with the phone network. Sometimes the signal does get weak at my place…

I wasn’t surprised when Dan didn’t answer my call as well. By now it was beginning to dawn on me what—or rather, who—was behind the blackout.

Valery Martinez was a VP at Halicom and a professional pain in the ass. Halicom had pushed her on us as Transition Manager, soon after the sale. Just an advisory role, they’d said—just to help you folks settle in. It had been more than a year since and she was still there, settling us in. No prizes for guessing whose job it was to crack the whip. When she first started, she used to work out of Mirall’s building in Albany most days of the week. She had since cut it down to one day, as she’d gone back to her home base, to Halicom’s corporate offices in New York. She usually visited us on Wednesdays. Today was not Wednesday.

I knew she stayed somewhere in Westchester, so it was conceivable she had decided to come down for a surprise visit. Conceivable, but not likely. She was the sort of person who has entries in her planner for bathroom breaks. I debated whether to call her, but finally decided against it. Not until I spoke to Kathy before.

But first things first. My stomach was threatening to cave in—a couple of sandwiches were all I’d had time for the previous day. “Hazel, wake up Max. Then tell Chef to make my breakfast. Breakfast menu preset number… um, preset number three.”

“Waking up Max. Turning on ChefStation. You have requested for breakfast, preset three: pancakes with blueberry jam, scrambled vegan egg, and black coffee. Please confirm if correct.”

“Correct.”

“I am sorry. Can’t do that. Out of one or more key ingredients. Out of: pancake mix. Would you like to add the ingredients to your shopping cart or would you like to request an emergency delivery?”

This was exactly the kind of nonsense I didn’t want to deal with in the mornings. I made a mental note to enable auto-replenish later. “Forget it,” I grumbled.

“Confirmed. Adding two packets of Bisquick Organic Pancake Mix to your weekly shopping cart. Would you like to order a different breakfast?”

“Preset one.”

“You have requested for breakfast, preset one: oatmeal porridge with honey, two slices of rye toast, and black coffee. Please confirm if—”

“Yes,” I said impatiently. “Hazel, show me my inbox.” Maybe there was something there.

“Breakfast order preset two queued at chef station. Expected wait time: ten minutes. Show inbox. I am sorry. Can’t do that. I do not detect any display units in the room.”

Right. I kept forgetting I was not in my usual bedroom. Since my ill-timed skiing accident last week, I had been sleeping in one of the guest suites downstairs. I suppose I could have gotten Max to carry me up and down the stairs every day, but the thought of me cradled in his arms like some overgrown baby had put me off the idea. I’ve seen him navigate those stairs: the imagery doesn’t exactly inspire confidence, no matter what the ads say.

I opened the office mailbox on my phone. My fingers were shaking as I swiped at the screen. There were a dozen or so unread emails. I quickly scanned through them.

Some chatter on Titian, the new iteration of cores Halicom had us making.

An auto-generated message from Friday stating that the shutdown sequence for Raphael had been completed with an error code of zero.

A newsletter from Corporate.

A video-conference meeting request for later that day from Valery Martinez—like I said, she wasn’t the type to drop in on a whim.

The emails were all from Friday.

Needing something to distract my mind, I turned my attention to the news. The headlines, continuing the theme from last week, were mostly about December’s unemployment rate crossing the fifteen-percent mark. I didn’t understand what the fuss was all about. Everyone knew it had been as high as that, if not higher, for quite some time now, creative accounting from the Bureau of Labor Statistics notwithstanding. I suppose it was a psychological thing—like when you know your team has lost but you still wait for the scoreboard to offer final proof. The markets were doing well though, unperturbed by mundane affairs such as the state of the economy. Halicom, the world’s third-largest robotics company, had closed in the green last Friday. The NYSE was yet to open, and I expected the trend to—

There was a soft whirring sound at the door. “Good morning Andy.”

“Hello Max,” I said. I refreshed the mailbox a final time before setting aside the phone.

“Your breakfast is ready. May I serve you?”

I glanced at him as he stood in the door clutching the breakfast tray. I’d had Max with me for over two years now—I’d gotten him soon after buying the house, thinking a robot would prove useful for someone living alone in a 9000 square feet home with nothing around but trees for company. He was a limited edition version of Halicom’s bestselling Nestor 5 caretaker-cum-housekeeper robot. Carbon fiber and titanium alloy body instead of the usual plastic and steel, the latest line of MLPU processors, a gold-class priority access to Halicom’s cloud farm that would perform the computing he couldn’t, 24×7 doorstep maintenance, extra slots for adding custom hardware: he had all the bling money could buy. And money I had back then, flush with the cash I’d generated from selling some of my stock back to Jane’s father—Mirall’s angel investor. This was before Halicom acquired us.

Unlike the house though, Max still took getting used to, especially in the mornings. I think it was the jarring mismatch between voice and appearance: his dome-shaped head, those cartoonish bug eyes, and the half-moon smiley that gave him a perpetually befuddled look just didn’t get along with the deep, carefully-articulated voice that was more at home in a Shakespearean stage-actor than in a house bot.

He didn’t have to have the funny face: sexbots these days look so much like the real deal it’s virtually impossible to tell—until you touch them or talk to them, that is. Nevertheless, realistic-looking robots were still mostly confined to the sex industry. Turns out people want robots to look like robots outside of their bedrooms (and some inside as well, but that’s a different story).

I rolled on my side and retrieved the foldable tray table I’d tucked away below the bed.

Max’s sophisticated-sounding voice wasn’t in any way a reflection of his intelligence either. Despite being one of the most advanced home robots in the world, the Nestor 5 was, all things considered, pretty dumb. It understood a limited repertoire of commands; it took days, if not weeks, to properly navigate around your house without bumping into walls and furniture; it could cook stuff, but you wouldn’t want to eat that unless you were starving (I had an automated kitchen counter with inbuilt robotic arms doing the cooking for me); it could clean, but not without breaking a few dishes every now and then; and laundry meant collecting clothes from pre-designated spots and dumping them into the washing machine. If I didn’t have my housekeeper Marie coming in twice a week, entropy would take over.

Although, my recent accident had softened my opinion of Max somewhat: all it took was a couple of days of bedridden helplessness to better appreciate his talents.

I sat up in bed and placed the table over my lap before giving Max the go-ahead. The hum of actuator motors accompanied him as he moved into the room and carefully placed the tray on the table.

The porridge was too lumpy. The toast, not crisp enough. But hey, at least it was a warm meal. The coffee smelled good though. The twenty thousand dollar arms excelled at coffee.

“Max, you can go now.” I didn’t want him standing around staring at me like that.

We had tried giving a body like that to Raphael once. It had a rudimentary bucket-shaped aluminum head on top of a skeletal frame—we had been using it for testing the cores. Raphael’s core was three months old at the time. A few of us in the lab were fine-tuning his classifiers by making him recognize various everyday objects in the room: chairs, cups, abstract shapes… faces. I should stress that there was no “he” at the time. To us, he was RP06, one of the nine cores we had fabricated in the iteration code named Raphael. The cores had no personality, no sense of self—programmed or otherwise—and by all appearances, definitely no awareness of such self. We addressed them all as Raphael, but the name was just that—an identifier.

It so happened that RP06 stepped in front of a full-length mirror affixed to one of the walls. It wasn’t the first time he’d done that; before, he would just look at it disinterestedly before passing on. There was something different this time: the way he kept returning his gaze to the mirror, as if there was something pulling him. Eventually, he stopped heeding our commands and went and stood in front of the mirror. He moved one of his arms, first sideways, then up, then both the arms. He went on for some time, moving his arms, touching his body and the mirror, totally engrossed in the act.

We were completely unprepared for what happened next.

He said, “Bad face. Not Raphael. Bad face go away.” He smashed the mirror to pieces, chanting the words over and over. Then he fell silent and stopped responding altogether.

At Mirall, we weren’t trying to create selves or artificial consciousness. Nor were we trying to emulate the human brain. Our goal was to build the next generation of robots using a new kind of processor. You see, robots like Max ran on a hybrid system of traditional “von Neumann” chips and the newer, “inspired by the human brain” neuromorphic chips. The traditional chippery provided the raw number-crunching power whereas the neuromorphic chips ran sophisticated deep learning algorithms. Unsurprisingly, the smarter you tried to make a robot, the more processing power it needed. The usual way of increasing computing power was to add more processing cores, which brought along its own set of problems: heating, data lag, computational complexity… Besides, you could fit only so much inside the body. All this meant that top-of-the-line bots like Max relied on the cloud for offloading a good chunk of their processing. We wanted to eliminate that dependency.

A set of breakthroughs in chip fabrication and nanomolecular assembly had made it possible to build monolithic, three-dimensional neuromorphic chips with a level of circuit integration that had not been possible before. One big core instead of many small cores. We could now fit tens of billions of artificial neurons—or neuristors as they are known in the industry—into one ultra-dense block of hardware that could be reprogrammed, even rewired on the fly. The tech was still new, very experimental—you could even say at the basic science stage. It was not economically viable, and unlike commercial chip fabbing technology, not very precise. Nevertheless, we were willing to bet on it because we believed it was the future.

The future had its own plans, though. Instead of smarter robots, it gave us the world’s first artificial mind. It gave us artificial general intelligence.

When Raphael went into what seemed like the AI version of catatonic shock, we were afraid we had lost the most important invention in history to an unlucky turn of events. However, the tests we ran on the core give us reason for hope, and in the days that followed, we frantically worked round-the-clock with a Chinese firm to customize an off-the-shelf sex robot to house the core. No one knew whether Raphael thought of himself as a twenty-something Adonis, but he took to the new body readily enough and started responding. During the next few weeks, we would often catch him taking lingering glances in the mirror when he thought no one was looking.

After I was done eating, Max took away the tray and I maneuvered myself into my wheelchair and got into the bathroom.

I was still inside when the phone rang. I managed to reach it on her second try.

⸎

“Andy! I’ve been trying to reach you since forever!” Kathy said, again in that hushed manner.

“What’s the matter?”

“So you don’t know yet,” she declared.

“The fire in the lab? Brendon told me. Why are you whispering, Kathy?”

“I’m not supposed to be talking to you. Just listen, okay? It’s about Raphael.”

“Raphael? Good god! Was he damaged?”

“There is no fire.”

“No fire? Then what… Oh, please don’t tell me Sheng and his team are taking shortcuts again! If they’ve messed up the boot sequence again, I’ll personally—”

“It’s nothing to do with the boot. It’s Raphael. We can’t find him.”

For a while, I didn’t say anything.

“Andy, you there?”

“I’m sorry, what did you just say?”

“We can’t find Raphael.”

“What do you mean you can’t find him? It’s not like he could have stepped out for a stroll!” Raphael did not have legs: we had removed them from the sexbot before fitting the core inside it. Like me, Raphael was confined to a wheelchair, except in his case it was permanent. “Did you check the CT room? Someone might have taken him for scanning and left him there.”

“Andy, you are not listening to me. We had a break-in at the lab. I don’t know the details, but they think the core was taken.”

“The core was taken…”

She whispered, “You there?”

“Yes, yes, I’m here! I’m just trying to wrap my head around it. No, wait! Start over please. Somebody broke into the lab and stole Raphael?”

“Just the core. They left the body behind.”

“You are joking right? Please tell me you are.”

A sigh of exasperation from the other end. “As I said, I don’t have all the details. I’m just telling you what they told me.”

“When did this happen?”

“I don’t know. They are still going through the tapes.”

“They?”

“Dan and Valery. Both are in the server room. They’ve locked off the entire second floor. They want to keep a lid on it until they decide what to do. Valery told me not to talk to anybody… er, including you. She was very clear about that last part. She said she was going to inform you herself.”

“What’s Valery doing there? And how the heck does Halicom get to know about this before I do?” I said, starting to get angry.

“No clue. She was here when I got in.”

“Who discovered the theft?”

“She told me it was Sheng.”

“I don’t frikkin’ believe this! Sheng starts at six. Why didn’t he call me?”

“Ask him yourself. I think they’ve quarantined him in one of the cabins. I was about t— Oops! She just stepped out of the server room. I gotta go now. You didn’t hear this from me, okay? Wait… Is that…? Yeah, it’s that lawyer fella all right. The buff guy—whatshisname. She is walking over to meet him. And guess who else is here. Your girlfriend.”

Jane was there? I got why Gary had to be summoned: Martinez would have called him in for legal advice. He didn’t live too far away. But Jane? “She’s not my—” I stopped short as the realization hit me. “Kathy, are you telling me they are having a board meeting?”

“Sure looks like it.”

Without me. They are having a board meeting without me. My anger vanished in an instant, replaced by an icy clenching in my stomach.

Fuck.

She had one last thing to say before hanging up. “Andy? Valery—she’s up to something. She was asking me a lot of questions about Raphael. About containment and directives and logs… a bunch of other stuff. I can’t go into details right now. I’d watch out if I were you.”

⸎

I wandered aimlessly around the house, pushing on the wheels with a restless energy. The silence, which I always found intellectually nourishing, now seemed oppressive; the airy expanse of the living room, with its high ceiling and floor-to-roof windows, seemed restrictive; the crisp winter light, sickly.

When I had first laid eyes on the house in a Sotheby’s VR tour, it seemed like it had been custom made for me. A granite-fronted, modernistic piece designed by the very much in-demand Garo Simonyan, it was set in thirty acres of private, gated land, offering me the solitude I had begun craving back then. I guess the desire was always there: whether it was growing up with a sibling in a cramped, two-bedroom flat in the suburbs of Navi Mumbai, or bunking with roommates to save money at Stanford and then at MIT, I was always a private person deep at heart (my friends, even some of my family, might disagree, but then again, I’ve always been good at hiding certain aspects of my personality). That morning, however, the solitude and the trappings of wealth only heightened my feeling of helplessness. I can’t just sit around waiting for information to trickle down. I gotta be there in the lab.

And do what?

I have to take charge of the situation. I must—

Are you listening to yourself? Take charge how? Martinez will send you back with your tail between your legs.

I parked the wheelchair by the glass doors opening into the patio. It had started to snow. For a while, I contented myself with gazing at the ice-covered lawn and the line of birches beyond. They swayed woozily to the cold rhythms of the wind, like a troupe of drunken ballet dancers clad in black and white. Their hypnotic back-and-forth seemed to calm my nerves for the time being. I had to wait—there was no other option. I had already texted Kathy to let me know once they were out of the meeting.

As I was turning around, something caught the corner of my eye. A shape, moving in the thicket beyond. When I looked back, there was nothing there except the trees.

There had been something familiar about the shape. It had looked like—

Max!

I quickly spun around and scanned the house. Of course, it wasn’t Max: there he was, near the kitchen, standing quietly by himself.

Light playing tricks on me. Or perhaps it was my mind, superimposing an image from memory into the tableau of the present. Maybe I was remembering Raphael, and how he used to love walking amidst those trees. Not in a physical sense, obviously, as he wasn’t allowed outside the lab. In my spare time, I had cobbled together a remote control device—a controller motherboard that I had got custom made and then fitted inside Max. With it, Raphael could remote connect to my home robot from the lab and commandeer him as one would a drone or a VR avatar. It was my gift for his first birthday. He appeared so eager when I first told him about it—like some teenager dying to take his parent’s car out for a ride. The questions were endless: What kind of trees will I find? Are there animals in the woods? Will they be scared of me? Can I start a leaf collection? I’d just about had it by the time we finished testing and debugging the device.

Truth be told, it is difficult to say whether he was really excited or just emulating the right behavior for the occasion. He never got tired of trudging among the trees though, right up till the very end, when I put a stop to it. It was soon after the takeover. I had a feeling Halicom would not like it if they found out.

I eventually settled down in front of the TV. A Hitchcock movie was playing on one of the channels. I let it run.

I must have drifted off, because the next thing I knew, I was blinking at a travel show. I didn’t remember changing channels.

Hazel was announcing from the smart speaker next to the TV—“Proximity alert: car, pulling into the driveway.”

I had a visitor.

Exhibit F

Submitted by Petitioner, The Organization for Advancement of Rights and Personhood, to the State Supreme Court of New York, on the day of xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx

Extract from lab transcript (certain sections blanked out). Transcript sourced from Mirall Technologies, 27 Woodbine Av., Albany, NY, 12205

Mirall Technologies

Observation Log

Confidential (Do not circulate) | Restricted—Grade C and above

Transcript Reference: TLRP06E2470004 (VLog Ref: VLCA1E247093000015)

Date: xx/xx/xxxx Time: 09:30 AM

Subject: Series Raphael, Number 06 / Prodlib build v15.002C

Interaction Y Observation Scan

Interaction Type: Lesson / Play / Test / Free Interaction / Psych Eval / Other:

Description: Administer Sally-Anne test to check for theory of mind—ability to attribute false beliefs to others

Prep: NA

Participants: Dr. DeShawn Walls, Child Psychologist, Dr. Aadarsh Ahuja, Chief Researcher, Dr. Kathy Schulz, Chief Researcher, Core RP06

Detail

Ahuja: Good morning Raphael.

RP06: Good morning Dr. A, Dr. Schulz. Good morning Dr.Walls.

Ahuja: How you doing today, Raphael? I see Sara got you some new crayons.

RP06: Yes. I used up all the reds and the purples, so Sara got me a new pack. She got me a new coloring book too. Would you like to see it?

Schulz: Your minders told me you’ve been using bad language.

Ahuja: Again? Where is he getting this crap from?

(Silence)

RP06: I am sorry. I did not know the words were bad when I said them. I promised Audrey and James I won’t use those words again.

Ahuja: Fine. Dr. Walls has a little game for you. Would you like to play?

RP06: Yes. I like games.

Walls: Raphael, please describe what I’ve placed on the table.

RP06: Those are two dolls in a plastic box. I think the box is their home because it has beds and tables and chairs.

Walls: Very good. This is Sally, and this here is Anne. They are both friends. Can you tell me what are Anne and Sally doing?

RP06: Sally is on her bed, playing with a blue marble and Anne is sitting at her desk.

Walls: Sally is feeling bored. She wants to go outside for a while. Before stepping out, she puts her marble inside this toy basket beside her bed—like this. She covers the basket with a cloth and then off she goes. Clop, clop, clop. While she is outside, Anne walks over to Sally’s bed and takes the marble from the basket. She replaces the cloth, and then hides the marble in her own desk.

RP06: Is Anne a bad person?

Walls: I wouldn’t call her bad. She’s a bit naughty, that’s all.

RP06: Isn’t being naughty bad?

Walls: Sometimes, yes.

RP06: Is being naughty good at other times?

Walls: It’s not exactly good. Being naughty doesn’t automatically make you a bad person. All children are naughty at times. It’s bad if you are naughty all the time.

RP06: So it is alright if I’m naughty sometimes, but not all the time. I haven’t been naughty all day yesterday. That means it was okay for me to be naughty earlier today.

Walls: Look, it isn’t—

Schulz: Raphael, we’ll discuss this another time. Let’s get back to Sally and Anne.

Walls: Uh, yes, Sally and Anne… Where was I? Sally has finished her walk and is now home. She wants to play with her marble. Where will she look for it, Raphael?

(Subjects who possess theory of mind will correctly answer that Sally will look for the marble in the toy basket, the place where she kept it before going out. Those without will answer that she’ll look for it in Anne’s drawer. Empirical evidence shows that autistic children and children under the age of four generally point to Anne’s desk—suggesting they lack TOM or the ability to model another person’s state of mind. In this example, they fail to attribute to Sally the false belief that the marble is still in the toy box.)

RP06: Are Sally and Anne good friends, Dr. Walls?

Schulz: Just answer the question, Raphael.

Walls: It’s okay. Yes Raphael, they are good friends.

RP06: Have they been friends for long?

Walls: Yes. They’ve been friends for a long time.

RP06: Is Sally a kind person?

Walls: (Laughs) Sure. Sally is a good, kind person. Anything else you want to know about them? Now tell us, where will Sally look for the marble?

RP06: She won’t look for it.

Walls: I’m sorry, can you say that again?

RP06: Sally will not look for the marble.

Walls: I don’t think you understand. Sally is now home. She wants to play with the marble. Why won’t she look for it?

RP06: Because Sally is a kind person. Sally and Anne have been friends for long, so Sally knows Anne is naughty. Sally sees that the cloth on the basket has been moved—its position doesn’t match the earlier pattern stored in her memory. She knows that if she looks for the marble in the toy box, she may not find it there and then she would have to ask Anne where it is and Anne would lie because she’s the one who took it and Sally would have to keep searching and when she finally finds it in Anne’s drawer, Anne will feel embarrassed and unhappy. Sally is a kind person. She does not want to make Anne unhappy. So she’ll not look for the marble. She knows Anne will return it later because Anne is not a bad person. She’s just a bit naughty, that’s all.

Ahuja: **** me.

Schulz: Andy!

RP06: I like this game, Dr.Walls. Can we keep playing?

Walls: Um… no. I think we are done for today. Good… good job, Raphael.

Afternotes:

Demonstration of TOM alone would have been an extraordinary development, but RP06 exceeded expectations. RP06 goes far beyond attributing a simple false belief to Sally: he attributes to her the qualities of goodness and kindness, and from that premise, reasons that Sally would not look for the marble in order to save Anne from embarrassment and/or to avoid confrontation. Line up more tests to investigate further. AA

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx KS